A 5 to 10-minute read, depending on your speed. In this second (of three) ‘About Money’ articles, you’ll learn about the first two of four factors to consider when deciding what level of investment risk to take – on each of your financial life goals.

These ‘About Money’ articles are written to help all (new, recent and experienced) investors because we must all ensure that the risks we take on our investments are right for our personal situation.

What did we cover in the first ‘About Money’ article?

In the first ‘About Money’ article, ‘How much investment risk is right for you’ we:

- Showed why it’s impossible for anyone (however smart they claim to be) to advise you on investments from a blog, book or video! Your adviser needs to be qualified AND know all about your personal circumstances and ambitions.

- Outlined the ten foundations of personal finance to sort out – before you consider investing.

- Explained why investments tend to produce higher returns than cash savings – over the long term.

- Illustrated the effect of a small extra return – over the long term.

- Warned of the extreme risks of aiming for much higher returns than mainstream diversified funds can deliver.

- Pointed to the overwhelming choice of (140,000) investment funds and why analysing those is the wrong way to approach this.

Be sure to read that first ‘About Money‘ article before continuing here.

Can we super-simplify our fund choices?

Clearly, we must be careful when trying to simplify complicated topics – which investment most certainly is.

However, in this (and the final) ‘About Money’ article, we want to equip you with four simple factors to consider when investing – to help you navigate these opaque (and often dangerous) waters.

We’ll start to explore those four factors in a moment.

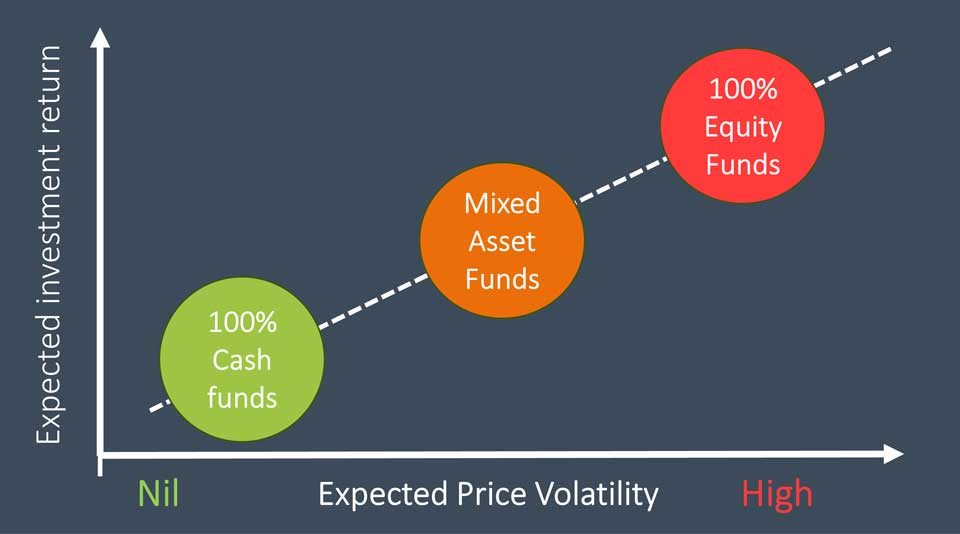

First, you need to know something about the spectrum of risks and (potential) rewards from investing – as we show here.

This (extremely simplified) chart seeks to show that you can expect much better long-term returns from investing (when compared to cash-type funds) if you can accept more volatility (or bumpiness) in the value of those investments over time.

The chart assumes that you make good fund selections.

You should also be aware that with poor fund selection, you may get poor investment returns and high levels of volatility – the worst of both worlds!

Also, be aware that there are no guarantees that even the best funds will deliver high returns.

We’re simply saying what financial theory suggests – which is that higher-risk investments (normally) get priced at levels which offer the potential for higher rewards.

What do the three coloured circles show?

100% cash-type funds – bottom left.

These funds aim to protect the value of your capital in nominal (£/$) terms and are useful, for example, when you expect to withdraw some or all of your money from your investment (or pension fund) in the next few years.

These funds tend to hold bank deposits and other ‘safe’ assets, like short-term government bonds. For that reason, their long-term returns tend to struggle to keep up with inflation.

100% equity funds – top right.

(Equity is the commonly used word for shares or stocks)

Pure equity funds aim to generate a higher total return than cash-type funds (and inflation) over the long term.

And well-managed, diversified and fairly priced equity funds tend to deliver on that aim.

You just have to accept that the value of your investments may go down (quite a lot, from time to time) as well as up.

Between cash and equity funds is a range of ‘mixed asset’ funds.

Mixed (or multi) asset funds typically aim to reduce the risk to investors (versus pure equity funds) while offering the prospect of ‘better than cash’ returns.

And, as their name implies, these funds may invest in a mixture of various asset types, including Cash Deposits, Government and Corporate Bonds, Commercial Property, Equities and Commodities.

With this simple (three-part) model in mind, let’s now explore the first two of these four factors to consider when making investment decisions.

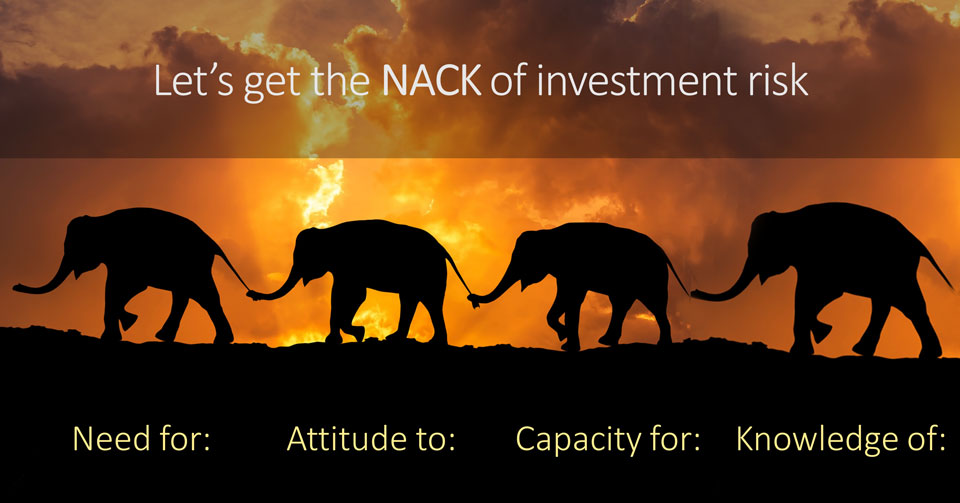

This is about developing a NACK for investing!

Remember (from the first ‘About Money’ article), we assume here that you already have (or have decided on) some good value investment and/or pension boxes for your money.

If you’re unsure how to choose the right boxes (to set up or keep) read our series of ‘About Money’ articles on that.

Now, we’ll start to explore the factors you need to consider to decide how much investment risk to take on each of your financial life goals.

Keep this (NACK) framework in mind as you develop a new financial plan or review an existing one—on your own or with an adviser.

Financial advisers use different words to describe these four factors, but all qualified advisers agree that they must be considered.

We’ve simply labelled these factors this way to make them easy to remember.

You might also want to ask your family and friends if they know about the NACK of Investment – and if you’re met with a blank stare, send them a link to this ‘About Money’ article.

Now, here’s the first factor we’ll explore, and it begins with the letter ‘N’.

N stands for the ‘Need’ for Investment risk.

The first question is the rate of return (and, thus, the level of risk) you need to take on your money. Here are some examples to bring this to life:

Example 1.

Suppose you are in your 60s, with five million pounds (or dollars) in safe bank deposits and government bonds.

And let’s also assume that you only want to draw an income of £30,000 a year.

In this case, you do not need to take much, if any, investment risk at all.

Yes, you might want to invest your money to continue building wealth—for yourself or as a legacy to others.

And, with that wealth, you might want to consider some planning to avoid unnecessary capital taxes – if those issues concern you.

However, we’re not covering tax and estate planning in this ‘About Money’ article.

The point here is that with substantial wealth, you do not need to invest the money to obtain a basic income.

Example 2.

Now, let’s suppose that, like most people, you have more modest levels of wealth, and you’d like it to grow faster than inflation over time.

In this case, you may need to invest some of your money – to achieve your goals.

If your aim was to build a fund of £100,000 (in today’s money terms) over 20 years from an investment of £50,000 today, you’d certainly need to invest that money wisely.

It’s extremely unlikely that you could achieve that goal by leaving the money in savings accounts.

Example 3.

Let’s say you were saving regularly to build a fund to retire from work a few years early – in, say, 15 years from now.

Based on reasonable assumptions (of 4.5% p.a. real returns), if you invested regularly (as opposed to saving in the bank) you could potentially boost the value of your escape fund by more than 40%.

Building a fund of 40% more than saving in the bank might be the extra money you need for a proper escape from work.

The numbers are even better over longer terms, of course.

For example, over 30 years, on the same assumptions, you might expect to build a fund of more than double that of bank account savings.

Just be aware of the reasonable limits to the additional returns from investing.

If you’re told you could earn much higher returns than four or five per cent over inflation (and there are plenty of scammers who will tell you that), then please take a second opinion on the advice you’ve been given.

As we’ve seen, very high returns may be possible, but only where you risk losing a lot of your money.

What if your financial life goal is unattainable?

If you’re using reasonable assumptions and your financial life goal turns out to be unattainable, you must decide whether to:

• Save or invest more money towards that goal.

• Give yourself more time to achieve it.

• Scale back your ambitions for (or delay or let go of) that goal.

Many of us are faced with this situation because we leave it too late to start saving for the future – and that’s a topic for another day.

Just be aware that ‘ramping up your risk exposure’, in the hope of achieving much higher returns, is a very risky approach.

A is for Attitude to Investment Risk

Confusingly, your attitude to risk is sometimes called your risk tolerance or risk appetite but they all broadly measure the same thing.

Your adviser, if you have one, can provide you with a questionnaire to assess your attitude to risk.

Or, if you’re a ‘do it yourself’ investor, your investment platform should offer a risk assessment tool.

Unfortunately, there are many different risk assessment tools, and they don’t all measure your attitude to risk in exactly the same way.

Some assessment tools are better than others for measuring aspects of your financial personality (your composure and impulsivity, for example), although you can always discuss these areas with your adviser if you have one.

Either way, most of these tools will suggest a level of variability (or bumpiness) in your investment values that you’d be comfortable experiencing each year over time.

And, let’s be clear: there are no right or wrong answers here. As with other aspects of our personality, we’re all different.

A small proportion of people are uncomfortable taking any investment risk. They want to know their capital is protected (in terms of its value in pounds) at all times – even when it’s explained that bank savings may be eroded by inflation over the long term.

Conversely, some people are happy to take substantial risks on their investments in the hope of achieving higher returns.

And unsurprisingly, the attitude to risk of most investors sits between those two extremes.

So, you need to know your attitude to investment risk, but that’s not enough information on its own – to make sound investment decisions.

For that, it’s vital for you to understand your capacity for risk on each of your financial goals. And that’s what we’ll explore in the final ‘About Money’ article in this series.

Thanks for dropping in