This 10 to 20-minute read is the first of two ‘About Money’ articles for anyone who struggles to talk about (and deal with) personal money matters. And that’s most of us from time to time!

Here, we’ll explore the first five of ten reasons we might find it hard to talk about money with close friends, family, or a financial professional.

You’ll find the second five reasons here.

We doubt these ten reasons are exhaustive, so if you struggle to have valuable conversations about money for these or other reasons, we’d love to hear from you.

This is just one of many ‘About Money’ articles we’ll offer on what really matters for making good decisions about your money.

Now, let’s look at the first of these five reasons we don’t talk about money.

Reason 1. We don’t understand the basics

Our financial literacy problem is very well known, and it’s global, too.

The S&P Global Financial Literacy Survey tests 150,000 adults from 148 countries every few years with questions in four areas – like these.

On risk diversification

Suppose you have some money to invest.

Is it safer to put your money into just one business or into multiple businesses or investments?

On inflation

Suppose over the next ten years, the price of everything you buy were to double. If your income also doubled, would you be able to buy less than you can buy today, the same as you can buy today or more than you can buy today?

On numeracy (around loan interest)

Suppose you need to borrow 100 US dollars. Which is the lower amount to pay back: 105 US dollars or 100 US dollars plus three per cent?

On compound interest

Suppose you put money in the bank for two years, and the bank agrees to add 15 per cent per year to your account. Will the bank add more money to your account in the second year than in the first year, or will it add the same amount in both years?

Suppose you had 100 US dollars in a savings account, and the bank adds 10 per cent each year to the account. How much money would you have in the account after five years if you did not remove any money from the account: $150, more than $150 or less than $150?

How do you feel about those questions?

If you found them hard, don’t worry; you’re far from alone. According to the survey, being financially literate means correctly answering three or four of those questions.

Yet, in the last survey (from 2014), only one-third of adults (worldwide) passed that test.

Unsurprisingly, adults in developed (and more equal societies) tend to fare much better than those in under-developed and unequal countries.

Three Scandinavian Countries (Sweden, Denmark and Norway) topped the results table, with 71% of adults found to be financially literate.

In contrast, less than 20% passed the test in many less developed countries, with the lowest result in Afghanistan, being just 14% (less than 1 in 7 adults)

Financial literacy rates vary enormously, though, even among developed countries, as we see here:

- Sweden, Denmark and Norway 71%

- Israel 68%

- United Kingdom 67%

- Germany 66%

- United States 57%

- France 52%

- Japan 43%

- South Africa 42%

- Portugal 26%

Does this mean things are ok in the UK or the USA?

No, not at all.

Other research in the US suggests that financial literacy levels are going backwards. We also have dramatic examples of the problem in the UK.

For example, a 2015 (Ipsos Mori) survey asked people various questions about money, including this one on pension planning:

‘What pension fund would you need to provide a retirement income (including your state pension) of £25,000 a year?’

How would you answer that?

The range of answers given was quite extraordinary.

- Over half of those surveyed thought a fund of less than £150,000 would be enough.

- One-third thought a fund of £50,000 would suffice.

- And one in eight people thought a fund of £15,000 would do the job!

The correct answer, in 2015, was about £300,000! And, if you wanted that income to rise with inflation each year, you’d need a lot more than that.

For information: Updating the target pension in that question to today’s money terms, and taking account of increased levels of state pension and higher interest rates since 2015, would still mean you’d need to target a fund of nearly £300,000.

So, it seems we’re not as financially literate as the S&P survey suggested in 2014, and while the Mori Poll was in 2015, our pension knowledge is not progressing either.

Fast forward to 2023, and in Boring Money’s Pension Report (based on 4,000 UK adults), we learn that many people don’t know how their pensions are invested – between shares, bonds or property, for example.

But more shockingly, we learn that:

- One in five workplace pension savers don’t realise their pension funds are invested at all.

- And 92% (11 out of 12) of those surveyed said they don’t feel confident about taking basic actions on their pension plan, like switching funds or changing the amount they pay in.

Why don’t we understand money?

Financial literacy is an enormous issue, and we only have room to touch on it here.

In short, however, we see four causes of this problem.

First, we don’t have excellent numeracy skills in the UK (or the US), and you need some number skills (and to know what pension income rate to assume) to convert a target pension income into a required pension fund size – as in that question above.

Similarly, if you want to estimate the future value of a lump sum investment (or series of investments) over ten or twenty years, you need to know the formula to put into your spreadsheet. Alternatively, you must know which online calculators are reliable and use sensible assumptions. Not all of them do.

The second reason we struggle with questions about money is that (in the UK, at least) the basics are not consistently taught in schools.

Yes, some basic money management skills are taught in some schools today. But according to financial education teachers, what gets taught is a postcode lottery, and the chances of children being taught about money are currently falling, not rising!

Also, long-term financial planning topics are not taught in schools or even in business or economics degrees, which might explain why most people don’t have a clue about pensions.

So, as with other ‘life skills’, we think our schools and colleges could be better.

The third significant cause of confusion around money is Government policy.

The government defines the taxation and other features of our financial products (and strategies)—like whether government bonuses are added to our savings and any input or age limits for paying in or accessing our money.

The constant tinkering (by all governments) with the taxation of savings, investments, and pensions makes it hard to know which products are best for you.

We want to make this product comparison job easier for you. So, we offer another series of ‘About Money’ articles to help you decide which money box (or strategy) is best for you. And that’s a decision best made before you put your money into that place!

Click here to learn all about that.

Finally, for now, we think financial firms (banks, insurers, fund managers and financial product providers) must bear some of the blame for personal finance being so hard to understand.

We believe these firms should create better (more engaging) content to answer your key money questions in generic terms and stop tilting their messages to sell you their products before you know what you’re buying!

Of course, we know that’s a big ask, so we offer these ‘About Money’ articles to help you with that.

Reason 2: Few people know anything about financial planning!

If a new coffee shop opened in your neighbourhood, you’d have a rough idea of what products it would offer, in addition to cakes and sausage rolls.

But what if a financial planning firm opened in your area: could you describe its services?

Most people cannot unless they’ve worked with a good financial planner.

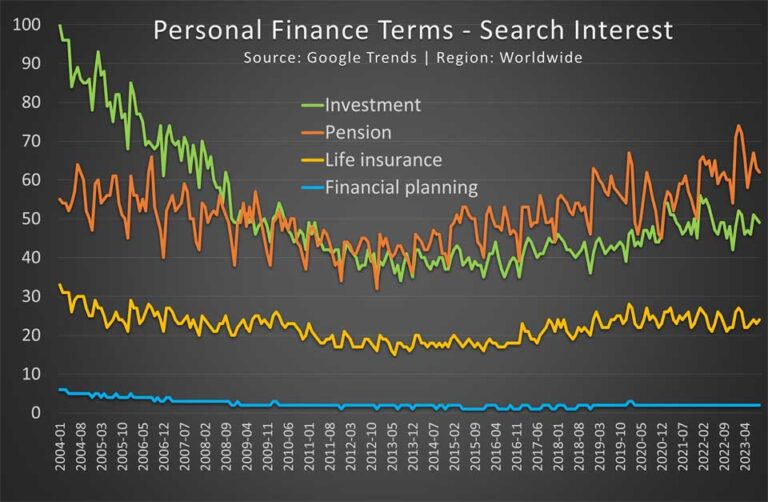

The evidence is clear and shown here about who searches for what (financial) services online.

Compared to investments, pensions, and life insurance, virtually no one is searching for the most valuable service – of financial life planning.

We tend not to search for things we know nothing about!

Very few people want to study the (tax, investment and charge) details of pension, insurance or investment products.

Frankly, those topics are incredibly dull unless you know how to bring them to life, as we plan to in our ”About Money’ programme.

What worries us, however, is that so few people know anything about financial planning – because that is the service most people need.

A conversation about your financial plan is about YOU and what YOU want for YOUR life… for yourself and your loved ones if you have some.

So, it’s vastly more interesting than discussing financial products or market prospects.

And if you want to have a conversation focused on your needs rather than financial products, you need to find a good financial planner.

Reason 3: We feel out of control when talking about money.

Few of us are comfortable talking about subjects we don’t understand.

Or, rather, we feel uncomfortable (and lose our confidence) once we realise we don’t understand something.

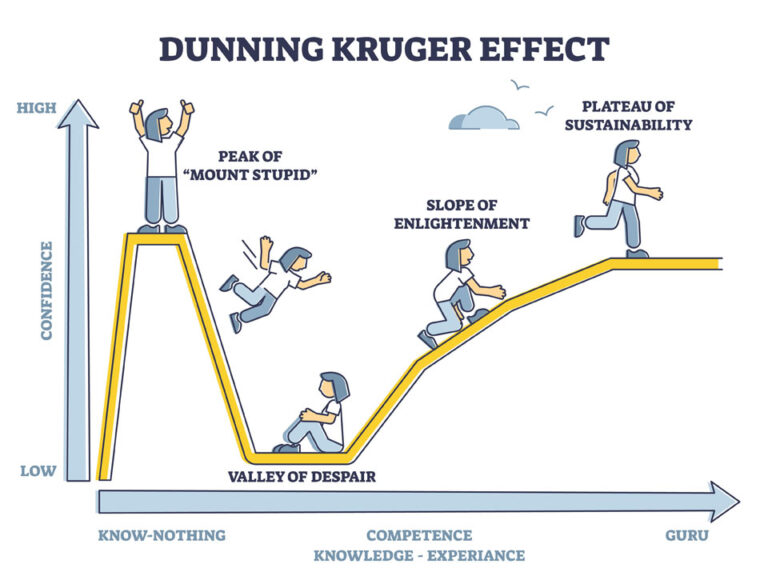

As Dunning and Kruger discovered, it can take a long time for us to learn (sometimes the hard way) that a little knowledge can be a dangerous.

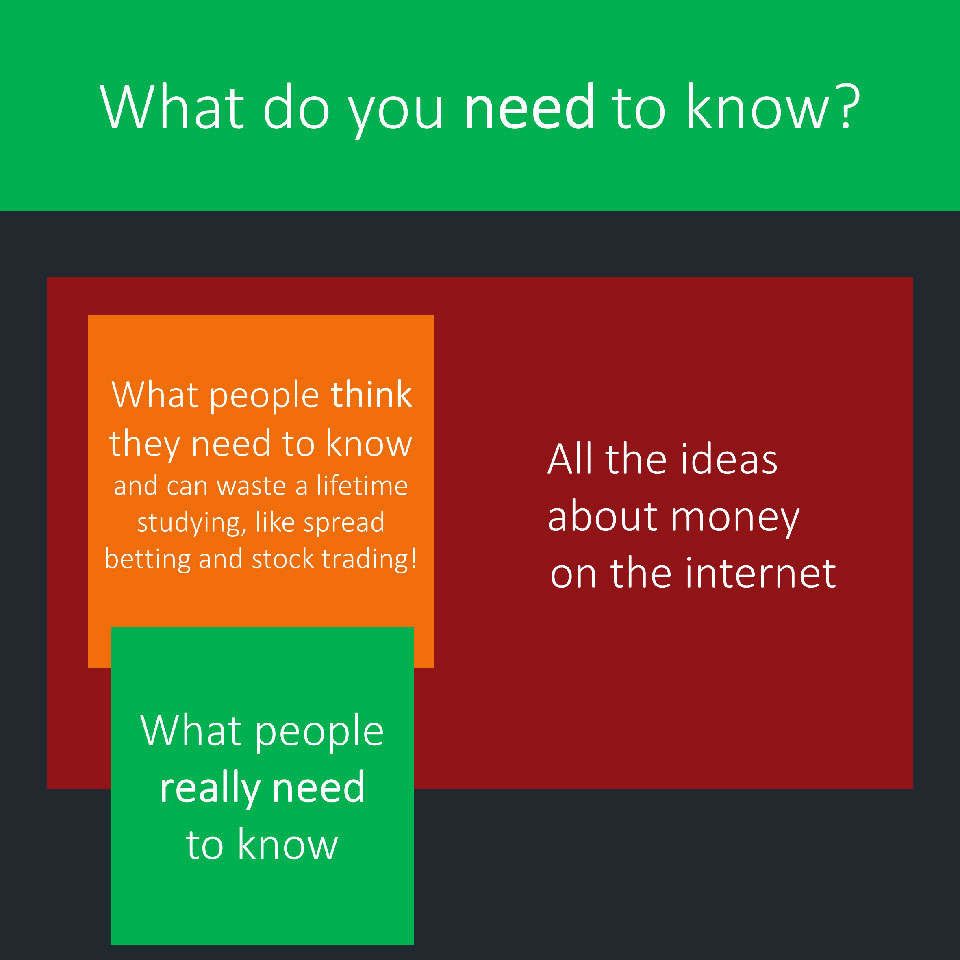

Clearly, it makes sense to learn enough to get past the peak of Mount Stupid and the Valley of (knowledge) despair.

However, to achieve that, we need to know what we don’t know about money and what we need to learn about.

And that’s what we’re here to help you with.

In future ‘About Money’ articles, we may investigate the Dunning-Kruger effect and other behavioural biases more deeply because they can lead to big mistakes in all areas of life. For now, be aware that the feeling of ‘not knowing what we’re doing’ can prevent us from discussing or taking action on vital money matters.

Fear is a natural emotion that seeks to protect us from harm – financial or otherwise.

Fear (for most of us) stops us from jumping into a car and trying to drive on the road before we’ve had any lessons. But sadly, it doesn’t always stop us from investing our hard-earned money in things we don’t understand!

The challenge is that so many people tell us to ‘ignore our fears’ and jump into their hot money-making scheme, and our natural behaviours make us susceptible to these calls.

• Our brains like to save energy (avoid overwork), so we always look for quick and simple answers to complex questions.

• We’re often too quick to trust others who don’t deserve that trust.

• We too readily accept instructions from those we believe are ‘authority figures’, as discovered by Stanley Milgram in some ‘shocking experiments’.

And those are just some of the reasons we make big money mistakes.

Just be aware – there are many psychological forces and behavioural biases that can lead us to make bad decisions. So we hope to come back to these topics in future.

For now, we’ll focus on how poor knowledge and skills can seriously hold us back.

We’ve known since the 1970s (from Psychologist Albert Bandura’s ideas on Self-Efficacy) that we’re more inclined to engage in activities we feel capable of.

We can all identify goals (things we want to achieve or change), but we also know that converting ideas into action is challenging.

Bandura and others have found that as we become more capable in complex tasks, we:

• Develop more interest in those activities and commit more strongly to them.

• Recover quickly from setbacks and re-frame our problems as tasks to be mastered.

On the other hand, when we feel unable to perform a task, we focus more on our failings, lose confidence, and avoid that task.

To learn more about the drivers of behaviour change, look at this brilliant model, which illustrates how our capability is critical to success. (The model comes from Social Scientist and author of ‘Tiny Habits’ Dr B.J. Fogg.)

In short, to make better financial decisions, we need knowledge of the financial planning process and the financial products we put our money into. Ideally, you’ll acquire this basic knowledge before investing, but it’s never too late to learn from trustworthy professionals.

The key is to avoid a path where all your lessons come from heavy losses in unsuitable investments.

Of course, you don’t need as much knowledge about personal finance if you have a good adviser, but we’d encourage you to learn the basic concepts so you know you’ve hired the right one!

And this leads nicely to the next reason we avoid discussing money – with advisers.

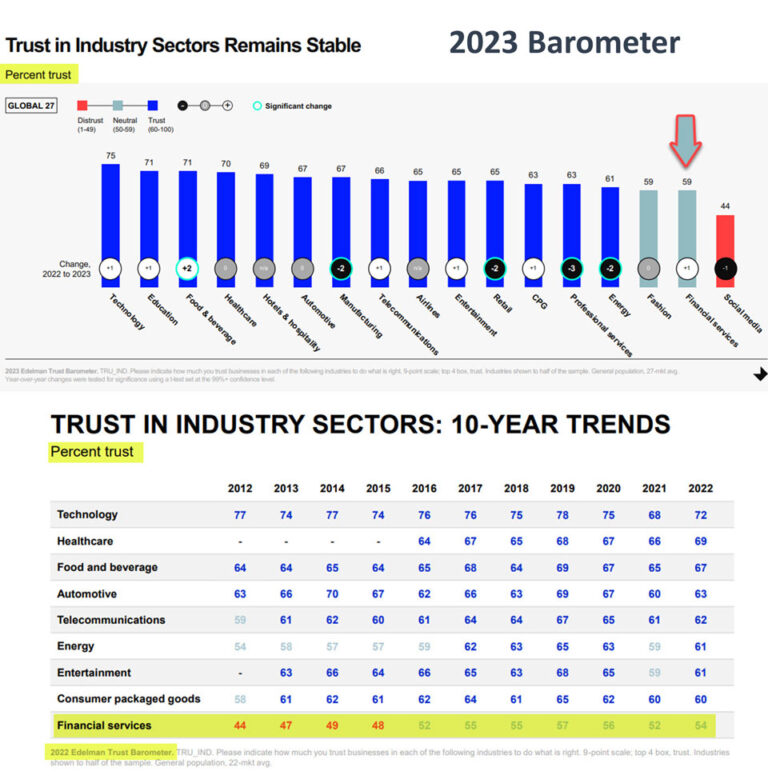

Reason 4: We don’t trust financial Service firms

The fact is that a great many people (worldwide) don’t trust financial service firms of any kind, so if you feel this way, you’re not alone.

As we can see here, the financial services sector (as a whole) performs very poorly in trust surveys like the Edelman Trust Barometer.

Looking at the UK, the 2023 Langcat advice gap report shows that 3 million more people would seek financial advice if they could find someone they trusted. The good news is that you should be able to find a good adviser if you know what to look for. That Langcat report shows that nearly 90% of those who take financial advice feel it represents good value for money.

The real problem is that there are not enough advisers in the UK to help a fraction of those 3 million people who feel they could use advice.

So, if you don’t yet have an adviser but are considering finding one, now is a good time.

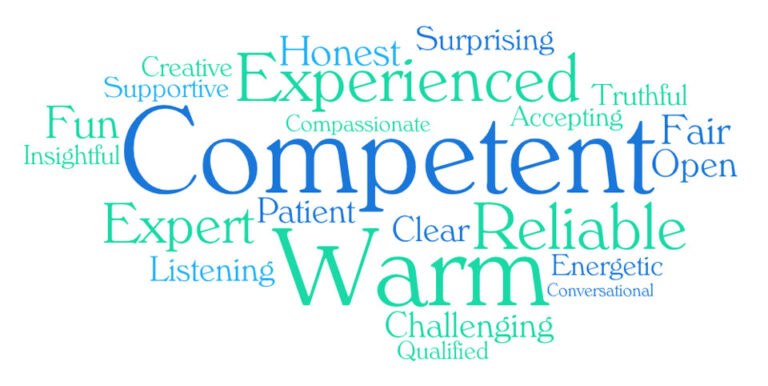

Trusting relationships are built on many attributes, as we illustrate here.

However, the evidence (Universal Dimensions of Social Cognition, by Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick) suggests that, for most of us, it’s the warmth and competence we sense that matter most for building trust.

Interestingly, Teddy Roosevelt observed the importance of warmth – long before the Psychologists proved its importance when he said:

“No one cares what you know until they know that you care.”

That’s a great quote but it also reveals a trap for the unwary. After all, if you focus entirely on how much another person seems to care, you may fail to check how much they actually know!

So, when choosing an adviser, we urge you to look beyond their ‘warm and friendly’ nature. And check that they’re competent in the areas where you need advice.

Reason 5: We fear we’ll lose control of our money

Finally, it’s worth noting that some people avoid talking to financial advisers because they mistakenly believe that the adviser will take complete control of their money.

Of course, a few people may wish to abdicate all responsibility for their money to an adviser. But we don’t recommend this approach – and a good financial planner won’t let it happen.

A good planner will work closely with you to design a plan to help meet your future needs and achieve more of your goals – for yourself and your loved ones.

YOU are the only person who knows all about YOU!

You are the expert on your circumstances, attitudes, and future ambitions. So, you will stay in charge of your financial plan – provided you engage with it. And if you know the basics about financial planning, you’re more likely to trust the process – and do what you need to – to make your plan successful.

Next steps

We’ve mentioned the Financial Planning process several times in this post, and we will outline that process for you in a future ‘About Money’ article.

In the meantime, if you don’t yet work with a financial adviser, think about when it would be a good time to start.

And don’t leave it too late – you never know what tomorrow will bring.

Thanks for dropping in