A 5 to 10-minute read, depending on your speed. This is the first of three ‘About Money’ articles to help you consider how much investment risk might be right for you – on each of your financial life goals.

These ‘About Money’ articles are written to help all investors (novice, recent and experienced) because we all need to ensure that the level of risk we take on our investments is right for us personally.

The #finfluenza epidemic

You also need to be aware that no one can answer the question of ‘How much risk is right for you?’ in a book, blog, video or Social Media post. Absolutely no one (friend, family member or #finfluencer) can tell you what’s right for you unless they fully understand:

- The financial planning process – and they are qualified to give financial advice.

- Your personal ambitions – for yourself and any others you want to help.

- Your current financial circumstances – and the outlook for the future.

- Your attitude to (and capacity to take) investment risks on your money.

Yes, some of the self-acclaimed financial gurus (on YouTube and TikTok) are entertaining. And some, if you know who to follow, understand some aspects of financial planning and investing.

The problem is that none of them know anything about you, so they cannot tell you what investments are best for you.

And they’re breaking the law if they try!

So, you need to take control of this process.

You need to consider the four factors we’ll cover (in the second of these ‘About Money’ articles) to work out what investment risk is right for you on each of your financial life goals.

All good financial advisers will consider these four points in advising you, and if you learn them, you can be sure that you do.

So, let’s get into this now.

Are your financial ducks all lined up?

Before you invest in anything that carries a risk to your money, you should have various financial foundations in place.

For those who need it, we’ll explore those foundations further in future ‘About Money’ articles. So, stay tuned for those.

For now, we’ll assume you’ve attended to all the basics, which means:

- You spend less than your income (from all sources) each year. And you have enough (accessible) cash savings for emergencies – like a temporary loss of work or expensive repairs to your car or your home.

- You’ve made arrangements to provide enough money to any financial dependents in the event of your death or serious disability. And your loved ones have clear instructions for dealing with your financial and material possessions in the event of those disasters.

- You’re on track to receive a full state pension, and you’re receiving any other state benefits you’re entitled to.

- You’ve paid off any credit card or other expensive debts.

- You’ve repaid (or you’re on track to repay) your mortgage before you retire.

- You have (or you’re building up) any additional funds you need (in bank savings or other low-risk funds) to pay for shorter-term goals like holidays, seasonal costs, and car replacement.

- You’ve designed a sound financial life plan. So, you know what you want your money to do for you (and any loved ones) in the future.

- You know how much money you’ll need, in today’s money terms, for each of your goals. And when you’d like to have that money available.

- Your cash and investments are held in the most suitable types of ‘money box’.

a. Examples of money boxes (or Tax Wrappers, as they’re sometimes called) include Pension plans, ISAs, Lifetime ISAs, General Investment Accounts, Insurance Bonds and more.

b. If you have money in the wrong box, you will miss out on FREE money from your employer or the government – as tax relief or savings incentives. And that makes it unnecessarily difficult to achieve your goals. - You’re not overpaying for these money boxes or for any advice on all this.

- If you don’t yet have all those ducks lined up, talk to a good financial planner.

- They will ensure you attend to those matters as part of your financial life plan.

Do you understand the basics of investing?

If you plan to invest (or already have money invested), you need to understand why investing (in ordinary company shares) tends to beat bank savings accounts over the long term.

So, that’s what we’ll cover first.

You could choose to buy a lot of (thick and complicated) books on investing. And, if you were lucky, you might find books that focus on facts rather than fiction, but here’s the theory in a nutshell.

The prices of company shares (and investment funds that invest in them) are driven by confidence about the future total returns (from capital growth and income) from those shares. So, share prices, like the collective mood of investors, are unpredictable.

Prices can sometimes, quite suddenly, move up or down.

Economic theory suggests that investors are rational and account for uncertainty when they buy and sell shares and other risky assets.

So, for much of the time, the buyers and sellers of shares agree on deals at prices where the expected returns from those shares are higher than those available on alternative safe investments, like bank savings or short-term government bonds.

Why would anyone invest in an asset where the value will move up and down, if they could get the same return from keeping money in the bank?

It’s this ‘rational’ theory of human behaviour that works, much of the time, in free markets. It gives investors an extra return (or premium) over cash savings in exchange for accepting a bumpy ride in their fund values.

At times, however, investors may move as a herd to drive prices higher (or lower) than many consider to be rational. And some dramatic price falls (or strong price surges) may follow these times.

You and your adviser, if you have one, need to assess whether the regular bumps and occasional deep holes in the investment road are cause for concern.

What’s the potential extra return from the stock market?

The extra return (above cash savings) from broadly based stock market funds has varied significantly over different time periods.

That said, on average, over 50 years, well-diversified (US and UK) equity funds have produced between four and five per cent a year (after charges*) more than cash savings accounts.

*Important notes:

Developed stock markets have delivered average annual total returns (including reinvested income) of around 6% p.a. in real (inflation-adjusted) terms before charges over the past 50 years. (Source: Schroders/Barclays Equity Gilt Study)

That equates to a real net return of 4.5% p.a. if we assume total annual changes of 1.5% (to cover fees for fund management, the financial product and platform and any advice). Charges vary on all of those elements, so take care to check yours.

Total returns on competitive savings accounts matched inflation over many long-term periods in the past, but not in recent years when interest rates were at historic lows.

The question you need to answer is this:

Does long-term investing, for the prospect of an extra return of, say, 4.5% p.a. above cash savings sound interesting?

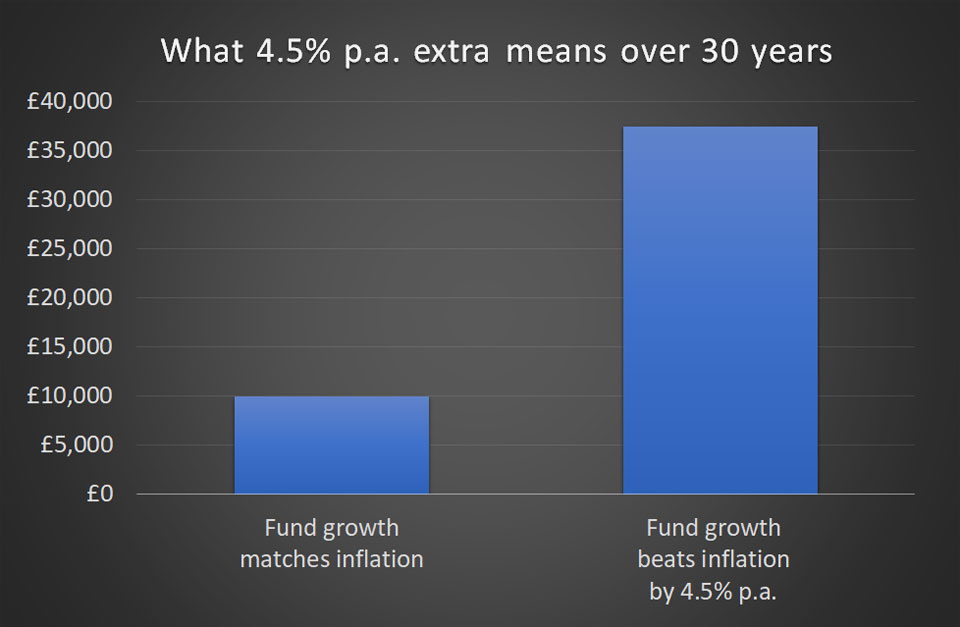

Many say not… until they learn that, over thirty years, in today’s money terms, it means you might grow your funds to nearly four times the value of a cash savings account. See here.

Additional notes to this chart:

We assume a lump sum investment of £10,000 grows in cash savings at the same rate as inflation. Which is why it remains at £10,000 in real (today’s money) terms in the chart.

By comparison, we assume that the stock market invested fund grows at 4.5% p.a. above the cash savings over 30 years.

Many people are surprised by these additional potential returns from investing over the long term – but these extra returns are clearly worth having, provided it makes sense to accept the short-term fluctuations in your fund values.

Just be sure to read the risk warnings on any investment illustration or promotion.

Past performance is no guide to future returns.

The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up.

You could get back less than you invested.

All investments should be regarded with a long-term view.

And refuse to invest in anything that does not carry that risk warning.

Why wouldn’t you aim for a much higher return?

It’s true that some investments might generate a much higher return than a well-diversified stock market-based fund.

However, straining your investments to deliver much more increases your risk of a permanent loss.

High-risk investments offer no certainty of more reward.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA: The UK’s Financial Regulator) warns that high-risk investments should be treated with caution.

Such investments are only suitable for experienced investors who fully understand the risks and are prepared to lose all of the money invested if things go badly wrong, which they sometimes do.

Examples of high-risk investment strategies include:

• Holding shares in just one company.

• Buying Cryptocurrencies – like Bitcoin.

• Investing in Mini-bonds – sometimes called high-interest bonds.

• Speculating in Contracts for Difference (CFDs) and Spread Betting accounts.

Overcoming the overwhelm – in fund choice!

As you’ll have noticed (from the section on getting your ducks in a row), making investment choices is one of the last things you need to do on your financial planning journey.

However, if you plan to invest any money at all, you (and your adviser, if you have one) will need to choose some investment funds at some point.

Investors generally choose ‘Collective Investment Funds’ to avoid the headache of selecting which particular shares to buy.

With mainstream Collective Investment funds (OEICs, Unit Trusts, Mutual Funds and Insurance Company investment funds), the fund manager selects the securities in the fund. (Or, with index-tracking funds, security selection is done by a clever computer program.)

The problem is that there are now around 140,000 investment funds to choose from, which is more than the number of companies listed on all of the world’s major stock markets!

That’s an overwhelming choice of funds, so the question is – how can you simplify that choice?

One way to approach this challenge is to simplify the Investment fund universe.

UK investors could learn about the Investment Association’s fund categories or the ABI Fund Sectors (for

Insurance product-based funds), which you can find here and here.

To save you time looking at all that detail, however, we’ve outlined the sort of investment categories you’ll find – here.

Of course, this is still far too much detail for most non-experts.

What’s more, this list doesn’t help you decide where to invest, does it? How would YOU choose between those fund categories and subcategories?

And, even if you knew which investment sectors were right for you, how could you select the best fund managers in those sectors?

What’s clear is that analysing funds directly in this way is extremely hard work for non-experts.

Thankfully, it’s completely the wrong way to approach this challenge, too!

So, if you’d like to know the right way to think about this, read the second of these three ‘About Money’ articles.

And learn how to work out how much investment risk is right for you.

Thanks for dropping in.